"Only a small proportion of the ocean of Buddhist philosophical texts that appeared since the Buddha (cca. 5th century BCE), deals with time specifically. In this essay we will go through six stages of classical Buddhist thought and examine their metaphysical claims regarding time."

Dharma Gate Buddhist University

A Doxography of Buddhist Views on Time in the Light of Analytic Metaphysics

Master Thesis

Supervisor: György Balikó

Written by: István Herdt

Budapest

2023

CONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. The concept of time in the Suttas and in Theravāda Abhidhamma

3. Reflections on the views of the Sarvāstivāda school

4. Time according to Nāgārjuna and McTaggart

5. Sēngzhào's Paradoxical View on Time and Change

6. Dōgen Zen Master and the Uji

7. Longchenpa's fourth time

8. Conclusions

References

1. Introduction

That the heart of philosophy is metaphysics is a defensible claim. One of the issues in metaphysics is the question of time. Thus almost every philosophical school has its own particular interpretation of time, although often it does not appear explicitly, but only as an underground stream that shows up sometimes here and there, in the context of other philosophical topics. In this essay we try to examine and compare the thoughts – with regard to time – of two metaphysical traditions, namely Buddhism[1] and analytic philosophy. We will not compare them in a strict sense, given that the original goal of this paper is the examination of the diversity of Buddhist philosophical views on time. But we have chosen a branch of Western philosophy, analytic metaphysics, as the tool for this examination. The reason behind that is threefold. Firstly, the conceptual framework of this philosophical tradition is perhaps easier to grasp; secondly, analytical metaphysics of time is also fascinating even in itself, and thirdly, that it is also exciting to compare philosophical approaches so far apart in time and space, and to examine one in the light of the other.

This would be fine, but the question may arise: why not examine analytic views of time in the light of Buddhist philosophy? In response, it could be said that because analytic philosophy of time is embedded in the conceptual–methodological fabric of Western philosophy, it is in this environment that the framework and conditions for such philosophical investigations are found. On the other hand, Buddhist philosophy is not embedded in a framework in a similar way. Yes it is – the objection might come – because Buddhist philosophy was born in a Hindu context. And that is true, but it has grown beyond that, outgrowing its own former inertial frame of reference to become a philosophy of equal magnitude and importance to the Taoist, Confucian, Hindu and Muslim philosophical traditions. These, in turn, do not have a shared (say, oriental) philosophical base, but if one deals with their philosophy, one does so via the methods and concepts of Western philosophy.

Now, time itself is not a central issue in Buddhist philosophy. Buddhism – like Christianity or Stoicism – is a soteriological teaching with a philosophical literature that fills whole libraries. Only a small proportion of the ocean of Buddhist philosophical texts that appeared since the Buddha (cca. 5th century BCE), deals with time specifically. In this essay we will go through six stages of classical Buddhist thought and examine their metaphysical claims regarding time.

Our tool of investigation, as mentioned above, will therefore be 20th and 21st century analytic metaphysics. It's better if first we are familiarizing ourselves with that. It started with Kant and Hegel. German idealism and especially Hegel and his system of thought acquired a great reputation, which trespassed the borders of Prussia and reached British shores with Thomas Hill Green and others in the third quarter of the 19th century.[2] Green was an influential teacher of philosophy, and his pupils, F.H. Bradley and Bernard Bosanquet enhanced the thoughts of German idealism, especially Hegel's, and interpreted them in their own particular way.[3] They are regarded in the history of philosophy as the greatest thinkers of the school of British Idealism.[4] They were respected by many, including J.M.E. McTaggart, also a Hegelian,[5] who built a detailed and sophisticated metaphysical view which he expounded in his two-volume magnum opus, The Nature of Existence in 1921 and 1927 (first and second volume respectively). But even before this work was published, he wrote an article in 1908 for the journal Mind entitled The Unreality of Time, which is still his most famous and most quoted work. This article has been widely quoted in analytical circles, throughout the twentieth century and up to the present day. It is interesting to note that analytic philosophy emerged in opposition to the very school to which McTaggart belonged,[6] yet his theory became popular amongst analytic philosophers. More precisely, it was not the theory itself that became popular, but rather the vocabulary, as we will see below. Let us take a glance now at McTaggart's philosophy of time and the concepts he used.

He was exposing his argumentation mainly in his above-mentioned works. In his article he starts with distinguishing two aspects of our perception of time. One of them describes an event as future, present or past – where the observer's constant 'now' is emphasised, which is dynamic and its direction of progress is towards the future. He calls the sequence of events along this process 'A-series'. The other aspect is the B-series, where the events are positioned in relation to each other in the earlier-later relation. But McTaggart argues that both our perceptions of time are illusory, because these series cannot really exist. He starts his argumentation with the assertion that change is essential to the existence of time.[7] In a world without change there would be no time either. Yet in the B-series change takes place in the form of an event ceasing to be an event, while a new event is forming – but that cannot be, since an event always remains an event. The same is true for the sequence of moments following each other, if we assume that time exists this way. These moments cannot cease to be a moment or transform into each other, thus change is not possible. There is only one way by which change is possible with regard to events (or moments), and that is from the perspective of the A-series, namely that a thing is getting closer in the future and getting further away in the past. So, any change would only be a change in the characteristics of the events due to their presence in the A-series. Thus change cannot be in the B-series, even though the earlier-later dichotomy surmises temporality. Consequently, there can be no B-series where there is no A-series, because without that there is no change, and therefore no time. The unchanging sequence of timeless events is the C-series, where the events, like days in a calendar, follow one another in a certain order, but this order does not require the presupposition of time or change any more than the order of the letters of the alphabet.[8] McTaggart further argues that the origin of the B-series is the combination of A- and C-series, and therefore it is sufficient to disprove the existence of A-series (past, present and future). He is doing that the following way:

On the one hand, if being present means that something simultaneous with its assertion, being future is later than its assertion, and being past is earlier than that, that implies that time would also exist independently of the A-series, which we have already seen that cannot be true. Otherwise, if being present, past, and future are temporal characteristics belonging to the A-series, than only one of them can be true for an event (or moment), the other two must be outside of the time series. Why? Because if we attribute such a temporal characteristic to an event, we would have to attribute the other two to it at the same time (and there can only be one at a time, it is impossible that something is past and future at the same time). If we attribute to it only one, e.g. 'the meeting tomorrow is in the future, but tomorrow it will be in the present and the day after tomorrow it will be past', then we see that we have set up another (imaginary) A-series,[9] but the present moment (and the A-series with it) in McTaggart's sense is objective,[10] and we cannot move it arbitrarily – or we can, actually, but it will be only our imagination, not the real, metaphysical present of the A-series. So it cannot be true to say that we are in the past from the perspective of tomorrow's meeting, because this past (depicting today or the present moment as past) is fictional, and the real past is not this, but yesterday (or the previous moment). This objectivity also makes it impossible for an event to have all three characteristics at the same time, since it cannot be past, present and future at the same time. The assumption of the A-series is therefore self-contradictory and thus the A-series cannot exist. Consequently, neither change nor time ultimately exists, and what we experience, the passage of time, is an illusion.

We should also note here that – obviously – McTaggart was not the first philosopher who denied the existence of time, it was quite a general view in British Idealism, Bradley and Bosanquet were also time-deniers.[11] We just outlined the arguments here, the series A, B and C are the ones that important for us, because these are the basic concepts that were used in the English-speaking world by many philosophers later.

With philosophers like Bertrand Russell, G.E. Moore and C.D. Broad a new, time-realist generation appeared, who claimed that time does exist, but that raises more questions: Does the present move? Which series exist, A or B? etc. One time-realist view is eternalism, also known as the B-theory. Bertrand Russel held this view, he claims that a proposition is either false or true, and it is always like that. In other words, a proposition (all of them) has an unchanging truth value. Some of our propositions seemingly change their truth value depending of the time of their utterance – for instance 'The cat is sleeping on the chair.' But if the date and time of this statement is indicated, than the truth value does not change. According to this view of time, there is no A-series (pastness, presentness, and futurity), only earlier and later, that is the B-series.[12] C.D. Broad's argumentation follows a similar line[13] to Russell's: in propositions like 'The cat is sleeping on the chair,' in ordinary speech we omit the words or phrase referring to time, but it is understood and assumed (e.g. 'now', or 'at this and this particular moment'). There are also statements, whose truth value is completely independent of time, e.g. 2+2=4, and there are statements which, whenever they are stated, they have unchanging truth value, because they refer to the occurrence of their content in time. Broad gives an example of the latter: “Whenever it rains, and I am out without my umbrella, I get wet.”[14] [15] Starting from such a linguistic basis (that a true statement should always be true) was reasoned that the B-series should exist.[16] As we have seen, McTaggart said that any change must be in the A-series. Contrary to this, Russell and Broad argued that there can be change in B-series (especially since the A-series doesn't exist), but it is not the events that change. Because the event is the change itself, in which certain things lose certain qualities and acquire new ones. This is change, and it manifests itself in the variety and replacement of the characteristics of things, not in the "change" of events.[17] Russell thought that change is when an object has different attributes in different times.[18] An apple can be yellow on Monday, than brown on Sunday.[19] According to B-theory eternalism, in addition to the three spatial dimensions, the fourth is time,[20] and that wherever things are located in these four dimensions, they are equally real.[21] Just as 'here' is not a metaphysically special place, neither does 'now' have an ontologically privileged status.[22] Things extend not only through space but through time too, and when we see something at a certain time, we just see 'a slice' from its whole being.[23]

There is also an A-theory view of time, that claims that the A-series is real, therefore we are using the words past, present and future correctly – in the sense that there is ontological difference between the three. Maybe the purest form of A-theory is presentism. According to presentism, only present things exist really. There is no hidden realm of the universe where future things await or past things are stored.[24] Of course we mean something when we say past or future, but the presentist does not refer to them as a certain part of spacetime, but as a set of certain propositions.[25] The present is the only time that exists, past and future exist only conceptually.

A different A-theory view is called the growing block theory. C.D. Broad introduced this idea first in 1923. He – and many others after him – claimed that the past and the present are what really exist, only the future has no real existence. With each present moment, another batch of existents is added to the sum of existents.[26] The present things had no pre-existence before,[27] they appear from nothingness. They have no ontological status whatsoever, before their formation – in this he agrees with presentism, but the latter rejects the existence of the past. The reason for accepting the existence of the past, Broad argues, is that there is a difference between change when something future becomes present and change when present becomes past. In the former case, change is not a literal change, since for a change to take place, the thing undergoing the change must exist both before and after the change. In the future, on the other hand, there are no things at all, so it is absolute becoming, in his words. But in the case of things going from present to past, the change is literal and things continue to exist as past things.[28] [29]

The third kind of A-theory is actually a view that combines A- and B-series, and that is the Moving Spotlight theory. It says that just like in B-theory, past and future things exist too, but the present has a distinguished ontological status for it illuminates a certain part of the spacetime-universe, and that is what we perceive as present. This speck of light then moves on to other things later, what we call the future, and the past is the group of things (beings, events, objects, thoughts, etc.) that were once illuminated.

After this brief summary of analytic views[30] on time we might start to examine their Buddhist counterparts.

2. The concept of time in the Suttas and in Theravāda Abhidhamma

If we proceed chronologically in the history of Buddhist thought, the first unit to be examined is the Pāli Canon, which is the set of canonized Pāli texts preserved by the Theravāda school. The Pāli Canon contains what are most likely the oldest accounts we have of early Buddhism and of the Buddha himself.[31] Within this collection of the Buddha's teachings, the first text in the Sutta Piṭaka is the Brahmajāla Sutta, in which the Buddha lists 62 erroneous metaphysical views. These views cover in principle all the metaphysical views[32] that could ever be conceived,[33] but none of them speaks about time specifically. However, the first four places contain views that deny change. These are called sassatavāda, or eternalism,[34] that is not to be confused with the eternalism of modern analytic philosophy. For eternalism here means that the soul and the world are an unmoving unity and that change is illusory.[35] The commentary literature equates this view with Advaita Vedānta[36] and its vivartavāda (lit. the teaching of illusion or modification) doctrine, that states that change is merely an illusion, caused by ignorance.[37] This being a false view, the Buddha's standpoint therefore must be the opposite of this, namely that change is real. It is not very surprising, for we know that it is a fundamental Buddhist teaching that impermanence (anicca) is one of the three characteristics of the world – the other two being unsatisfactoriness (dukkha) and essencelessness (anattā). Believing in the reality of change indicates a dynamic time-realist view, at least that much we can certainly claim by studying the suttas. There is no philosophical discussion about the existence or non-existence of time, or past and future in the Sutta Piṭaka. The Buddha speaks about time in completely ordinary language, always emphasising the importance of the present. This is, in fact, the normal, ordinary, dynamic conception of time, where time flows from the future, through the present, to the past. This is the dynamic view of time as we use it in speaking about time, A- and B-series together. In our everyday life, we think of both as real attributes of time,[38] and we have a handy conceptual toolbox to help us navigate on these two planes of time. This natural view of impermanence in the Buddhist teaching is not based on philosophical considerations but on experience of the ever-changing nature of the world.[39]

The doctrinal importance of change, however, gave way for subsequent Buddhist thinkers to develop a more elaborated view on time: the theory of momentariness (khaṇikavāda). This view became more refined in the Abhidhamma – that is the itemized exposition of the Buddha's teaching in lists and definitions – and its commentarial literature. The doctrine of momentariness divides time into separate, tiny parts, which, as they are formed, disappear, giving way to a causally successive one. It is a series of these moments – khaṇa in Pāli – that we perceive as "flowing" time.[40] But only the present khaṇa is real, the moments of the past and future are non-existent.[41] Because past by definition designates something that is already passed, ended, and we use future for things did not come yet.[42] A thing cannot be existent and ended or existent and not-yet-come in the same time, so past does not exist, neither does future. These divisions of time cannot really exist, for if they existed in the same way as the present, we would not be able to distinguish them.[43] So goes the argument. The Theravāda view is entirely consistent with the modern presentist claim that to exist in the present is to be real.[44] What "was" or "will be" cannot be called existent.[45] Unlike modern presentism, however, in Theravāda Buddhist philosophy of time there is no problem in postulating a relation between past and present or present and future – that is, existing and non-existing. This is constantly seen in Anglo-Saxon discourse on time as a problem of language, especially in the case of presentism. How can we make true claims about the past or the future if they do not exist? In contrast, the question of time in early Buddhist thought is closely connected to the question of sabhāva, or intrinsic nature. According to the Theravāda tradition, the ultimate building blocks of reality are the dhammas – these are phenomena that appear for one khaṇa, then disappear, giving way to the next set of causally subsequent dhammas. Now, only dhammas have this intrinsic nature, and therefore they exist ultimately, everything else exists only conventionally.[46] Sabhāva, however, lives for only one moment, and after its time it ceases to exist, together with its dhamma.[47] This also gives us a picture of a dynamic time, and this view of momentariness can be equated with a presentist view, that states the same propositions.[48] Thus, dhammas of the past and of the future are completely non-existent,[49] just like past and future themselves – there is not even a past or a future that is empty of dhammas, like empty containers. The words past and future are useful conventional concepts, but beyond that, they don't have any existence.[50] In western philosophy, this is called the reductionist or relationist view of time.[51] According to reductionism, time and space don't exist in themselves, they are just relations: there are spatial distances amongst material things, and temporal distances amongst events.[52] There is no separate entity we can point to as time (or space), only relations. Here, time is not a being that enables change, on the contrary, change plays the fundamental role, it's just that we tend to imagine time into change, because of its practical uses.[53] None of the Buddhist schools accept substantivism, meaning that time exists as a separate entity that contains things.[54] Thus the dhammas of the present are the only reality according to the Theravāda view, and they are in constant motion[55] from the non-real future towards the non-real past,[56] but without any pre-existence and afterlife,[57] due to the momentary nature of sabhāva. Only one dhamma has a non-momentary sabhāva, and that is nibbāna. Nibbāna's intrinsic nature is without becoming, change or destruction, so nibbāna – enlightenment – is timeless.[58] That's why the post-canonical Pāli text, the Milinda-pañhā states that time does not exist for the enlightened.[59]

It can certainly be said that Theravāda has always taken a presentist stance, partly as an imprint of the debates with the Sarvastivāda school (see later) and partly because Buddhist teachings place great importance on the present moment, and this is reflected in the metaphysical prominence of the present moment.

3. Reflections on the views of the Sarvāstivāda school

The Sarvāstivāda school was present in northern India from about the 3rd century BCE and was the dominant Buddhist denomination in the region until the 7th century CE.[60] The name means "the doctrine of everything exists." Perhaps their case is the only one in the history of Buddhism where the doctrinal distinctiveness of a school is derived from their view of time. The Sarvāstivāda school had a well-developed and rich Abhidharmic literature, of which the doctrine of everything exists (sarvaṃ asti) was an important part. This "everything" in their case meant past and future dharmas. The Sanskrit word dharma is equivalent to dhamma in Pāli and is the collective name for the types of phenomena classified in different aspects by Abhidhamma[61] and Abhidharma.[62] There are 75 such dharmas according to the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma, with concepts such as color, sleep, desire, diligence, or space, just as in the Theravāda.[63] But time as a separate entity is not found in the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma either. It is important to note that the Sarvāstivāda also maintains a relational understanding of time, it does not posit a separate existence for time as a substantivist would do.[64] However, the past and future dharmas do exist. The dharmas are the real existents. The Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma distinguishes between two kinds of existence: objective (or material, real) existence (dravyasat), which only dharmas have, and conceptual existence (prajñaptisat), which all other things in the world have, meaning everything that are composed of dharmas – in fact, everything that is not an individual dharma.[65] Now every dharma has svabhāva,[66] that is, intrinsic nature – moreover, only the dharmas have such an intrinsic nature. This intrinsic nature is independent of time (unlike in Theravāda), so both past and future dharmas have it. But time is not a dharma, so it could exist as a mere conceptual construct (prajñaptisat). However, if the dharmas of past and future are real, then for the doctrine of the three times (traikālyavāda) do not actually need the past and future themselves to exist as an entity.

Because of their postulation of the existence of past and future phenomena, their view is therefore akin to eternalism of analytic metaphysics, which holds the existence of the B-series to be real. Where did this idea come from? Presumably from thinking about the functioning of karma,[67] according to which if an action has a consequence, or, to use a phrase preferred in Buddhist literature, a fruit, and the action is in the past but the fruit is in the future, it is not possible for the cause to be non-existent once the effect exists, since the latter cannot arise from the non-existent – and the same is true with regard to the future. The presentism of the Theravāda school (and most of the early Buddhist schools) held to the non-existence of future and past, and rejecting this seemingly obvious argument, they explained the workings of karma in a different way. That is the seed theory, according to which actions leave certain seeds, or imprints, in the stream of consciousness, which transmit the information to the dharma that follows them in the next moment and then to the one after them, and so on, until the action can have its effect when the constellation of conditions are right.[68] But the question may arise, if we accept the doctrine of the three times, what is the difference between the three times? If past and a future exist too, why can we only act in the present, what differentiates it? This question, which was also asked by other Buddhist interlocutors, was answered by the Sarvāstivāda school with the concept of kāritra. Kāritra (meaning activity) is a characteristic of a dharma that enables it to have an effect – it exists only in the present. Past and future dharmas do not have kāritra, they have only latent agency (sāmarthya).[69] The present is distinguished from the future and the past by the presence of the kāritra.[70]

This privileged status of the present in the B-series, that is the superimposition of an A-series on B, brings the Sarvāstivāda school into closer affinity with the Moving Spotlight theory of analytic metaphysics. The difference is that the spotlight has no activating function, we just call the present whatever the light is on. However, the idea that the kāritra makes the distinction between the three times can lead to interesting conclusions. For the question arises, if each dharma has a separate kāritra, is it not too much of a coincidence that everything is simultaneously "right now" in the kāritra phase? Why are the kāritras of each of them so synchronized? For it seems, according to the Sarvāstivāda interpretation, all dharmas have pre-kāritra, kāritra and post-kāritra phases. How come that everything we see is in the middle phase?[71] An appropriate response to this seems to be that we see them precisely because they are in the kāritra phase, since the capacity of kāritra to affect includes perceptibility. However, my sensory faculties are also made up of dharmas, so I can only perceive with them in the present, and I can only perceive the active-kāritra-dharmas of the present. But what would be the difference between the non-perceptible post-kāritra dharmas of Sarvāstivāda and the past dharmas (that are ceased, and thus also non-perceptible) of Theravāda presentism? The kāritra is meant to provide ontological prominence of the present, but this prominence may not be much different from the presentism of Theravāda, where the present is ontologically emphasized as existent and the past and future are non-existent. In order to explain karma, it is not necessary to assume the existence of past and future, since Theravāda presentism can also explain karma. And the dharmas in the pre-kāritra and post-kāritra phases are completely inaccessible, so the difference between them and the not-yet-existent and already-non-existent dharmas of Theravāda is imperceptible. In one respect we may discover a difference, the future, which according to Sarvāstivāda eternalism (B-theory) must be predetermined, since the dharmas of the future are "already there" in some way, whereas according to Theravāda presentism it is "not yet decided" what the future will be. This brings us to the question of free will, since B theory eternalism (and thus the Sarvāstivāda school) must reject it. At the same time, it should also be noted that Buddhist philosophy largely ignores the problem of free will.[72] Nevertheless, returning to the dharmas, Dharmatrāta, one of the four great ābhidharmikas (Abhidharma-scholars) of the Sarvāstivāda, exemplifies the transition of the svabhāva of the dharmas[73] from one time to another as a golden vessel (the future) being re-moulded into another form (the present) and then into another (the past), thus the intrinsic nature of the dharma remains the same, only its mode of existence changes.[74] This view does not include the kāritra, but it assumes the three temporal things to be of the same "substance", and that is different from saying that past and future do not exist.

This being said, the question remains: what does the pre- or post-kāritra phase dharma (in Sarvāstivāda eternalism) possess that the not-yet-existent and already non-existent dharma (in Theravāda presentism) does not? Because to the experiencer, they seem equally inaccessible and unperceivable. Past and present dharmas can contribute to the initiation of the dharmas of another causal series through their latent capacity (samārthya).[75] In fact, even the presentist Buddhist would not deny this, but would change the verb tenses in the statement: they have contributed (when they existed) or will contribute (when they come into existence). In any case, this problem is also a good example to demonstrate that the metaphysics of the early Buddhist schools was objectivist, in the sense that they asserted the objective existence not only of consciousness but also of the external world. In addition to the two classes of existence (dravyasat – real existents or dharmas – and prajñaptisat – conceptual existents), the 5th-6th century[76] Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma text, the Abhidharmadīpa, distinguishes two more, and thus a total of four types of existence:

- dravyasat – real existents – dharmas

- prajñaptisat – conceptual beings

- ubhayathā – both kinds – depending on the context, it can be real or mental, e.g. earth, that can be a mahābhūta, i.e. material element, thus dravyasat, or the concept of soil, which is prajñaptisat

- sattvāpekṣā – an existent that exists only in relation to something e.g. father-son, teacher-student, actor-acting

What is remarkable to note here is that the debate between the presentist schools and the Sarvāstivāda is "only" on the two subcategories of the first category. The present dhamma is also considered by Theravāda as "real" existent, the other three categories are posited as non-ultimate, conventional existents in the same way as in the Sarvāstivāda.[77] But in terms of time, they represent two different philosophies. It should be said that while the Theravāda branch of Buddhism (along with other early Buddhist schools) held the A-series to exist and thus can be said to be presentist, the Sarvāstivāda school held the B-series to exist alongside with the A-series, corresponding to the Moving Spotlight view.

4. Time according to Nāgārjuna and McTaggart

Nāgārjuna, founder of the Madhyamaka school, lived most probably around the turn of the 2nd and 3rd century CE in India,[78] and he is considered as one of the biggest Buddhist thinkers of all time. Nāgārjuna's major work is the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, which remains the central text and reference work of the school to this day. Chapter 19 of the work, the Kālaparikśā, deals with time. This chapter consists of six verses in which Nāgārjuna argues that time does not exist, at least not in the way our concepts refer to it. His line of thought can be summarised as follows:

If the present and the future were dependent on the past, then in some way they should already exist in the past. But we cannot find future time in the past. The present cannot be in the past either, because then it would not be "present". Moreover, these parts of time cannot be mutually conditional. If they were mutually conditional, they would have to exist simultaneously, just as the existence of a "father" implies the existence of a "child".[79] But they cannot be present at the same time for even a short time. Nor can these parts of time be independent of each other, since, for example, the present can only be located between past and future, nowhere else, and thus cannot be independent of them. In response to an implicit objection – that time must exist because it can be measured – Nāgārjuna says that only that which can be grasped can be measured, and time cannot be grasped. However, we cannot even say that it is changing, because then we would have to assume a time above the time in which the change occurs,[80] which would lead to infinite regress.[81] Moreover, time cannot depend on other things, because there is no existing thing in the world on which it can depend, as it has already been explained by the author in other parts of the work.

That part of the argument, that past, present and future are interdependent but mutually exclusive, therefore they are self-contradictory and therefore cannot exist, is very similar to that of McTaggart, who also used this method to argue for the non-existence of time.[82]

We have seen that Nāgārjuna refutes the existence of past, present and future, i.e. the dynamic view of time, that McTaggart's A-series, in which events and moments flow from the future through the present to the past. Does Nāgārjuna refute the existence of McTaggart's B-series too? According to the positive reading of the sixth verse of Chapter 19 of the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, time is nothing but the collection of relations between empirical phenomena. There is no time outside these phenomena and relations.[83] This fits the B-series of events, and also fits the relationalist view (time being distance between events). One might say that Nāgārjuna represents the static and reductionist view of time, because we find no objection to the validity of the earlier-later distinctions in this chapter. However, in Chapter 11, entitled as "Examination of the Initial and Final Limits", he refutes the very existence of the earlier-later relations as well. Because all kinds of beginning and end are merely artificially created conceptual designations and projections onto certain parts of a process, their existence is thus conventional and it is not possible to speak of beginning and end, life and death, nor of earlier and later, as ultimate truths.[84]

All this is a refutation of the existence of the B-series. Rejecting A and B, Nāgārjuna rejects the reality of time and change too, along with McTaggart. What is left is the C-series, which depicts the sequence of events without change, or temporality, but does not give the direction of succession.[85] [86] The C-series of events is not temporal,[87] and we do not find a critique of such a series of events in Nāgārjuna.

There is an opinion[88] that Nāgārjuna rejects the existence of time (past, present and future) even as existing at the level of conventional truths (saṃvṛti satya), but this comes from a misunderstanding of the two truths doctrine (satyadvaya or dvasatya) of Buddhism. We can see that Nāgārjuna did not deny the existence of the three times at the conventional level, since it is precisely those phenomena at the level of conventional truth that he deconstructs with his arguments leading to infinite regress and self-contradictions. He chose these phenomena of conventional truth precisely because they are conventional and everyday (like talking about earlier and later, or past, present and future events). Even though he breaks down into its elements and refutes the ultimate existence of these conventional concepts, he uses them with the utmost naturalness in his other works. How this can be? Because conventional truths are truths, and we just tend to devalue them in the light of ultimate truths. This devaluation is even more pointless as we remind ourselves that there aren't any ultimate truths in the philosophical system of Madhyamaka. So, for example, "time" and "movement", are existents belonging to the level of conventional truth.[89] Indeed their ultimate existence is refuted by Nāgārjuna in the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, and they are illusory, but they are of a completely different reality than, e.g. the horns of a cat or the current king of France, as the classic examples go. These kind of things are the ones that don't exist even at the conventional level.[90]

Time – like all other things in the world – has no real, ultimate existence in Nāgārjuna's thought. At this point the question arises, whether this is the same semi-existence, the same illusory nature that time has, as McTaggart think it has. To enable the comparison, it's worth to understand and see what kind of attributes a conventionally true, conventionally existing entity – like time – can have, what the characteristics of its (non)existence are.

Conventional truths are statements that require further interpretation,[91] meaning that they are useful and practical, but under serious analysis one can see that they are refering to empty things – things that lack any intrinsic nature, and they are dependent on other empty things. And the empty things are of illusory nature.[92] By analogy, from the point of view of ultimate reality, conceptual reality is like an illusion in our conceptual world – traditionally, the example of the dream, the mirage, or the magic trick is invoked.[93]

On the other hand, according to McTaggart, time – and thus its parts, past, present and future – belongs to a group of concepts and descriptions that describe something that is not real.[94] Like the Mādhyamikas, he also refers to time and change as illusion and appearance.[95]

But let us consider here for a moment, whether illusions are real or nonexistent. We can think of existence in a Meinongian way,[96] together with the Sarvāstivādins, that anything we can think or speak of, is already existent – at least in our head, as a thought, even if it is impossible for such a content to become a real object,[97] accessible to other senses too. If we use this concept of existence, we cannot think or speak about nothing, or the nonexistent – because it turns into something immediately.

But we can think about the nonexistent in a different way. Kant[98] gives us four categories of nothing, and this might help us to navigate amongst the different concepts of the non-existing time:

- Gedankending (thought-thing). An empty concept without an object. They are usually abstract cognitive entities.

- Mangel (lack). An empty object of a concept. These are observable things of the world, but their existence is based on the lack of something. If this emptiness (not in the Buddhist sense here) disappears, so do their existence. Common examples are the darkness (as lack of brightness), cold (the lack of heat), a shadow (lack of light in an area), or silence.

- Anschauung – its name can be a bit misleading, because it means viewpoint, but Kant classifies here space and time exclusively. He calls them empty viewpoints without objects, because temporal and spatial relations would not exist – or would not be perceptible to us – without the objects amongst which these relations exist. But since this concept is an integral part of Kant's philosophy of time, which is not the subject of this paper, and since in this paper we are discussing ways of non-existence of time by means of the other three concepts in this list, we will ignore Anschauung for now.

- Unding (absurdity). They are empty objects without a concept – thoughts or utterances which contain contradictions. The classic example is the square circle, or other impossible "things".[99]

These, as we see from the short descriptions, could be called illusions too, at least from the Buddhist point of view. Time as Gedankending is possible to accept for both Nāgārjuna and McTaggart, being a conventional and conceptual construction in both philosophies. And also we can conclude that the concept of time of both philosophers can also be an Unding, for they derived the nonexistence of time from the internal contradictions of our concepts referring to time and temporality. The same is the case with Kant's Unding, only that these internal contradictions are more striking in the usual examples of impossible objects, like McTaggart's fourth angle of a triangle, the Duke of London in 1919,[100] or the classic Buddhist examples of the flower growing from the sky[101] or the horns of a rabbit.[102] Just like them, the concept of time is also loaded with many contradictions, therefore it cannot be real, according to both Nāgārjuna and McTaggart. We can see the difference in the category called Mangel, however. It describes an object whose existence is based on the absence of something else. McTaggart has no corresponding idea regarding time, but if we interpret Mangel in terms of the absence of svabhāva, the inherent nature, knowing that according to Madhyamaka philosophy things are not simply without svabhāva, but can exist[103] precisely because they do not have it, otherwise they could not,[104] then it is clear that Nāgārjuna's concept of time can also be included in the category of Mangel. This categorization allows us to see the subtle differences in nature and origin between the two kinds of illusory time.

There was a great turning point with Nāgārjuna in Buddhist philosophy, and in thinking about time. He was a pioneer in denying change together with time. It is important to see though, that this denial does not state that "behind" our changing world there is a static, unchanging reality, or a timeless world. This is the case in McTaggart's thought, but this is not the case in Madhyamaka. The latter claims that our situation is that we tend to attribute a kind of existence to things, objects and actors in the world that they do not have. We tend to think of them as separate, autonomous beings that have some kind of essence. This is the existence, the mode of being that Nāgārjuna denies, showing that no phenomenon in the world has this, because all of them are inter-dependent and essenceless, and this way illusory. McTaggart's illusion is illusory in relation to the world of the pure spirit (spirit is his ultimate reality), while Nāgārjuna's is a standalone illusion.

But the colourful history of Buddhist philosophy of time does not end here, as in later centuries new Buddhist sages emerged who also had original ideas about the nature of time.

5. Sēngzhào's Paradoxical View on Time and Change

Sēngzhào was a Chinese Mādhyamika philosopher, who lived two hundred years after Nāgārjuna, at the end of the 4th and beginning of 5th century CE, in the early stage of Buddhism in China. He was a disciple of Kumārajīva,[105] the famous Central-Asian monk, who translated many important Mahāyāna texts to Chinese. Sēngzhào has left us four major treatises and several minor works. One of his treatises is the "Things do not change" (物不遷論, Wù bù qiān lùn), in which he argues against the real existence of change, more precisely for the union of change and permanence. He based his opinion on certain parts of the Daśasāhasrikaprajñāpāramitā Sūtra and Nāgārjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā.[106] His view on time, as expressed in his thesis, is not merely an exposition of the Madhyamaka position, but a particular and innovative interpretation of it, which can, however, fit within the Madhyamaka framework. For him, the unity of opposites is freedom from opposites, and hence freedom from extremities, thus this unity is the middle way.[107] Although he says that the idea of change should not be rejected in favour of permanence, it is permanence that seems to be the more essential and real of the two in his philosophy.[108] The roots of the idea of rejecting change, obviously, go back to Nāgārjuna, although Nāgārjuna did not substitute permanence for change.

An interesting feature of his treatise on changelessness and time is that he does not mention future in the text, only speaks about present and past.[109] It is perhaps more than mere speculation to say that he ignored the future because he considered it even more non-existent than past or present.

He argues the following way for changelessness: dimensions of time always stay the same, for we are able to directly perceive the phenomena of the world only from the present moment, never from the past (or the future, if we wanted to complete the argument). Things do not change, but are at rest, because past things are always in the past and likewise present things are always present. Things in the past are never non-existent in the past, but things in the present are non-existent in the past. Moreover, things in the past have always been in the past, not in the present, just as things in the present have always been in the present, not elsewhere (in the future).[110] Even though we perceive constant change, the present moment always remains present,[111] never becomes past (or future). So goes his argument. It feels as if he is talking about two things at once: the concept and "perception" of past and present, and the "content" of past and present. As if a substantivist were confusing time as a container and its contents. But Sēngzhào, as a Mādhyamika, cannot be a substantivist. So his statements must be interpreted as relationalist, according to which there is no distinction between past and past things. However, his statements are very much in contradiction with our everyday experience and our fundamental feelings.

His second argument is that things exist only for a moment, and not more, therefore it is impossible for them to move from one point of time to another, therefore they don't change.[112] He supports this argument in another of his works, the commentary to the Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa. There he refers probably to the Sarvāstivāda school, saying that if things were eternal, they would move from the future through the present to the past. If they moved like that, in the three periods of time, we could say they change. But since they aren't eternal, they don't change.[113] It is very likely that he was familiar with the teachings of the Sarvāstivāda, not least because his teacher, Kumārajīva was ordained first as a Sarvāstivādin monk, and only later converted to Mahāyāna.[114] Apart from that, it is unlikely that this school had a direct influence on Sēngzhào's philosophy.

However, there are three possible explanations for Sēngzhào's paradoxical theory. Several of them may be valid at the same time:

- According to the Buddhist theory of momentariness, everything that exists is momentary in the sequence of dharmas that flash up and perish instantly. Then if we claim that everything that was in the past was always there, this makes sense in relation to the present moment, since "everything" – which in this case means all things in the past – is reconstituted in every moment. Thus, in every moment, "past" and "present" take on a new meaning.

- To further unravel the paradox of the union of change and changelessness we can turn to Sēngzhào's interpretation of language and words. He says that one should not regard words as the ultimate and exclusive definition of their referent. Therefore, just because we call something existent does not mean that it is definitively and exclusively existent. In the same way, we can call things changing, but this does not preclude us from describing them as permanent.[115] The same thing can be existent (or changing) for an ordinary person, and non-existent (or changeless) for a sage.[116] And one of the reasons behind this reasoning might be, that his master Kumārajīva used more than one terms in his translations when translating svabhāva (intrinsic nature) to Chinese. He renders it as zìxìng (自性), lit. self-nature, this is the most common word for svabhāva in Chinese Buddhism, but he also translates it as dìngxìng (定性), determinate nature, and sometimes as dìngxiàng (定相), determinate form, as well.[117] Sēngzhào, and other later Chinese Mādhyamika philosophers inherited this vocabulary, and they used these forms in their works, which could have some influence on their thinking. Therefore if they refer to something as empty, they describe it as free from determinate nature or form.[118] This might shed some light to the contradictions and to the origin of Sēngzhào's view on the fusion of change and permanence – as a state of indetermination – as well.

- Another way of understanding the argument for permanence is to take Sēngzhào's interpretation of time as a description of the block universe of B theory. He writes in his treatise:

"As there is not even a subtle sign of going or returning, what thing can there be that can move? This being the case, the raging storm that uproots mountains is always tranquil (at rest), rivers rushing to the sea do not flow, the fleeting forces moving in all directions and pushing about do not move, and the sun and moon revolving in their orbits do not turn round. What is there to wonder about any more?"[119]

In this block universe of the B-series, as briefly mentioned in the introductory chapter, time is the fourth direction of extension alongside the three dimensions of space. This four-dimensional union of spacetime can only be imagined in three dimensions (just like a tesseract), and by subtracting one dimension from space, we take a block as a model, whose longitudinal extent is time. Along this direction, we can mentally slice the block into very thin slices, each representing a momentary unit. Each of these slices, when removed and examined, is a snapshot of the world at a particular moment in time. Like looking at a frame of a film reel of a two-dimensional (given that it is projected on a surface) film. When we "walk" in this world of frozen time, we see that everything is still. But even if we look at the whole block from the outside, we can't detect any movement. Just as the images on the film reel do not move. And to see things as they are (because that is how the enlightened sages see them) is obviously to see also the true nature of time, that it is merely a different extension of things, and thus, in the perspective of ultimate reality, everything is at rest, without change.

So where can we place Sēngzhào amongst the interpretations of time in analytic philosophy? As a matter of fact, according to the latter interpretation, no. 3, he must be an eternalist, but he denies change and thus denies time. More likely, however, is that he denies the A-series interpretation of change, and that he does not think that change is that "at certain points in the B-series certain things have different properties" (contrary to Russell and in agreement with McTaggart), i.e. he does not regard this as time. Therefore, some consideration needs to be given to his classification in our binary notation system. Perhaps the most appropriate way to do this would be as follows, given that the digits represent the past, present and future, which are the elements of the A-series:

000gb

Although we wrote at the end of the first chapter in the introduction of the notation system, that the letters a and b after the three digits are intended to denote which series the number 1 indicates the existence of. We do not see a 1 here, but we can extend the rules of notation to say that if there is a letter of a series next to a zero value, then the series is not recognized as temporal. As in this case. In Kantian terms Sēngzhào thought that time is a Gedankending. This is what the letter g in superscript tries to express. And we can assume that future could be an even more illusory thing inside this category. Traces of thoughts referring to time as Mangel (something existing by virtue of an absence of something else) or Unding (a concept containing contradictions) are not present in Sēngzhào's works though.

6. Dōgen Zen Master and the Uji

Dōgen lived in Kamakura-era Japan in the first half of the 13th century. He began his monastic life in the Tendai school but is now known as the founder of the Sōtō Zen branch of Japanese Buddhism. His major work is the Shōbōgenzō, and its 20th chapter is entitled Uji, and it is about time. The title (有時) is a word-play, read as one unit it means "sometimes" in Japanese, pronounced "aru toki". However, this word is made up of two characters. When they appear separately, they can be read as "u" ("being") and "ji" ("time", or "at a time" or "o'clock"). Dōgen takes advantage of this, reading and interpreting them as separate characters, thus transforming the word into the concept of "being-time".[120] This notion of being-time is one of the unique concepts Dōgen uses in his philosophy. At the very beginning of the chapter he states his most important thesis: things are time themselves, they exist not in time, they are time itself.[121] Uji is basically the expression of this unity of things and time.

Time, for Dōgen, is not some external force, but an inseparable feature of all things that originates from the nature of their existence.[122] In virtue of this ever-changing, impermanent and dynamic nature of all things, everything can unfold all of its properties and potentialities only through the process of impermanence. Therefore even the Buddha-nature of man can manifest itself only through impermanence. Moreover, Dōgen, following the insight of Huìnéng, the Sixth Patriarch of Chan Buddhism,[123] identifies impermanence with Buddha-nature.[124] Buddha-nature is therefore identical with time, and both are the mode of existence of all beings.[125] Consequently, time gains a soteriological significance in Dōgen. But if time and change are not different from things, then things have soteriological meaning, which in fact means that the whole of existence (everything that exists) has it. This does not add much to the analysis of his thought on time, nor does Dōgen's denial of time as an entity independent of things, because this is a general feature in Buddhist philosophy as a whole. But in any case (for the time being) we can take Uji as an expression of the relationalist position.

In addition to Uji (being-time), we need to familiarise ourselves with a few other words, because Dōgen liked to think about time using his own concepts. The most important ones are jūhōi (dharma-stage), kyōryaku (passageless passing), and nikon (absolute presence).

The jūhōi – 住法位, dharma stage – are momentary units of time-being, certain momentary configurations of dharmas.[126] We call these configurations of phenomena as "things", by which we mean common designations such as firewood and ash, to use Dōgen's example.[127] A jūhōi is basically the instantaneous position of a certain conventionally defined thing in a slice of the four-dimensional block universe (as illustrated in the previous chapter). To use the example of the cinema again, an object in the film is composed of the jūhōi moments found on the individual frames of the film reel. These jūhōi frames appear as causes and consequences of previous and subsequent jūhōis, but Dōgen, like Nāgārjuna, also regards the concepts of "before" and "after" as unreal. In this case, however, the jūhōi is not a slice of the B-series, but only part of C-series, and time is not anisotropic. Because when he says

"Once firewood becomes ash, it can no longer revert to firewood. Still, one should not take the view that it is ashes afterward and firewood before,"[128]

he is referring to the succession of things, but this succession is not temporal, it is like letters in a written text lined up one after the other,[129] but there is no temporality in them, they could be read in any order.

The next concept is kyōryaku (經歴 kyō: pass through, ryaku: to take place), or passageless passing.[130] This is the concept Dōgen uses to describe the movement of time, which can move in any direction, with no fixed orientation.[131] The transition can be from today to tomorrow, from today to yesterday, from yesterday to today, from today to today or from tomorrow to tomorrow.[132] In this way he is not merely describing the movement of time, but rather indicates that to exist is to happen, to pass, that to exist is not something static, not a state, but a process.[133] This, in turn, is contrary to the film-frame-like static nature of the momentary jūhōis. But this would not be a problem if these concepts were placed in relation to the two truths, as it is the usual practice in Buddhist philosophy, and one described reality conventionally and the other ultimately. But among these concepts of time, we find no such hierarchy of truth-value in Dōgen's writings.

Another interpretation of the concept that is able to resolve the inherent contradictions is that kyōryaku is not a metaphysical category, but merely a description of the phenomenon whereby we are able to relate our experiences to certain linguistically, conventionally defined notions of time, which may even be contradictory. For example, a memory of yesterday may include the concept of tomorrow, or what is marked "today" may be "yesterday" tomorrow, etc.[134]

The third term associated with Uji is nikon (而今 - lit. now). It means a particular moment in time, which is subjective, the present of the particular experiencer. We can talk about past and future in relation to the nikon, in this way it is related to the kāritra of the Sarvāstivāda school. The experiencer perceives the passage of dharma positions (the jūhōi) from the nikon, through the nikon. In this way this is the same as the present of the A-series.

"Even if I make myself think of tens of thousands of pasts, futures, and presents, they are now, they are the Now (nikon)"[135]

– writes Dōgen, and this means that both the past and the future can only be accessed from the present, their existence is "in" the present.

At the same time, we can also talk about nikon from the perspective of the Uji itself, and in this reading, every moment is present.[136] However, we also know that for Dōgen, the nikon is ontologically superior to the future (which derives from it).[137] In other words, the present of the particular experiencer occupies an ontologically higher status than his past and future.

It can thus be argued that Dōgen's general conception of time is dynamic despite the introduction of the concept of jūhōi, the dharma-stages. And although the dharma-stages are "arranged in a sequence", this sequence is not temporal, as we have seen, and must therefore be related to the C-series. It is on this C-series that the present of the-A series "moves", so this is practically a version of the Moving Spotlight view of time, in which the B-series does not participate. It is rather an interesting version, because the Moving Spotlight theory is virtually a compound of A- and B-series. It’s A-series part is that the present objectively moves, and we call past that was illuminated by the light and we call future that will be illuminated. Meanwhile, the surface on which the spot of light travels belongs to the B-series, and the objects on the surface, i.e. the different things and events in time, are indeed in a later-earlier relation to each other. This is the classic Moving Spotlight view. However, we can notice two differences in Dōgen: while in the classical interpretation the present is objective, equally applicable to everyone, in Dōgen it is subjective, because every single moment can be nikon, and the now of the individual perceiver is ontologically privileged. The second difference points to a peculiarity of the original Moving Spotlight theory. This theory relies heavily on the underlying model in which the light of the present illuminates certain parts of the stage, or reality. What it does not necessarily say, however, is that the parts of the theory from the B-series, the objects (meaning the events) are arranged on a rather flat and wide surface in the model. They do not form a series in this way, even though in a normal B-series it should be defined what is earlier and what is later. But in a big messy room, where do we start cleaning if there is rubbish and dirt everywhere? Wherever we want. On the other hand, if we have a long corridor to mop, we can't do it just any way, we have to start at one end and finish at the other. What we intended to illustrate with this example is that the metaphor of the Moving Spotlight theory does not include the element that the events of a B-series must follow a certain sequence, so it would be more fitting to use the example of a spotlight moving down a long corridor, whereas Dōgen's is the true, theatrical Moving Spotlight, with a large and wide area for the light to move, where the events have no inherent before-after determination, only past and future relative to the spotlight of the present. Taking all this into account, our most plausible notation would be therefore 111a for Dōgen's view, thus indicating the lack of a B-series.

7. Longchenpa's fourth time

Dzogchen (tib. rdzogs chen) is a form of Tibetan Buddhism. It's not a school of Buddhism, but a particular set of teachings with its own philosophical texts and practices, present mainly in the Nyingma school and in the Bön religion. Longchenpa (Klong chen pa) was a prolific writer and scholar of the Dzogchen tradition and lived in 14th century Tibet.[138] He wrote extensively on Dzogchen theory and practice, and he developed a unique view on time, introducing the concept of "the fourth time".

The "three times" in Buddhist circles mean past, present and future, but Longchenpa claimed that there is a fourth one too. To see its place in relation to the three "normal" times, we should examine briefly the basic method of Buddhist meditation. When Buddhists meditate, they try to avoid "dwelling" in the past or in the future – meaning to get involved thinking about past or future things – and it is preferable to stay in the present moment. Dzogchen, however, interprets this method in a slightly different way, and it says that one should stay not even in the present, because then the mind will be occupied with present things and thoughts.[139] So, when one does not dwell in any of the three times, that's when the "primordial nature of mind" can arise, and that is the authentic way of being (in the) present. And this non-dwelling in any of the times is the fourth time of Longchenpa, more precisely, the mind becomes the fourth time, that is beyond the other three.[140] The fourth time is also called timeless time, and Longchenpa equates it with the gzhi. Gzhi literally means basis, and according to the Dzogchen teachings this is "the fundamental ground of existence," from which saṃsāra and nirvāṇa arise. Saṃsāra, or the cyclic existence, and nirvāṇa, the liberation from it, exist only derivatively from this base, moreover, their existence is illusory like a magic trick, in the philosophy of Dzogchen.[141] Gzhi is in fact the ultimate reality. And as it follows from this, the existence of past, present and future is illusory as well,[142] and even "earlier" and "later" are not inherent in gzhi, they disappear altogether with causality,[143] thus the B-series is declared to be illusory and not ultimately existent. This view seems to be quite similar to Nāgārjuna's. However, while in Nāgārjuna the ultimate reality has no name and no properties, Longchenpa (along with other Dzogchen authors) writes at length about the nature and properties of the "basis of everything" (the gzhi).

The gzhi is not only the timeless time that transcends the three times, but also everything else in the world is its manifestation.[144] And these manifestations are illusory and conventional. The difficulty for us here is to what extent can an atemporal "time" be called time, when the very nature of time (by definition) is temporality? If something is timeless (and the gzhi is), then we can call it time, but that does not make it time. Another interesting point is that gzhi is always dynamic, never static. Now, if something is dynamic, it means that change is involved in its existence, and if there is change, there is time. An explanation may be that because gzhi is beyond our normal, conventional senses and thinking, we are not able to describe it adequately in our usual terms. This is one possible explanation for the seemingly mutually exclusive features that Dzogchen authors attribute to this ultimate existence.

Nevertheless, we can also see that the fourth time is actually a state of mind itself. For the fourth dimension of time, gzhi, is achievable through engaging in the practices of Dzogchen. This requires proper training, insight and exercise.[145] But if it is an experience, however superior, it can be placed in time like any other experience. It cannot be time in the same way as the present or the past because the experience of timeless time is individual, not shared.[146] Therefore, as an altered state of consciousness, it is similar to a dream, or a hallucination, or a mystical experience – because it is. Being an experience, it is still a version of the present.[147] For McTaggart's C-series is essentially the reality behind the false A-series and B-series, which reality can be accessed from nowhere else but the present of the experiencer.

To summarise, then, Longchenpa, like McTaggart and Nāgārjuna, denies the existence of the A- and B-series. Unlike Nāgārjuna, he names the reality of the series, which is gzhi – in McTaggart's case, it is the spirit.[148] The three times therefore do not exist, this way Longchenpa is a time-denier, and we can denote his view on time as 000g.

8. Conclusions

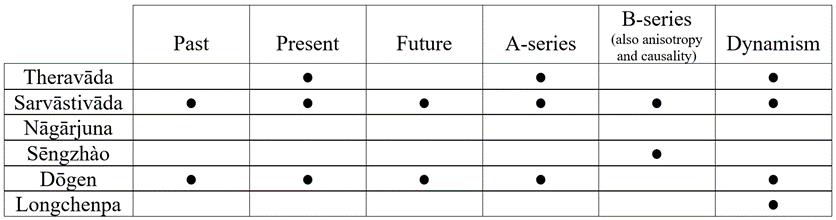

We have examined six Buddhist views of time, which can be denoted by the following notation according to the system we have introduced, where the three digits represent the past, present and future respectively, the letters in the superscript are abbreviations for the Kantian types of non-existence (Gedankending, Mangel, Unding), and the letters "a" and "b" indicate the existence of the A- and/or B-series in the given view.

Theravāda 0g10ga Sarvāstivāda 111ab

Nāgārjuna 000gmu Sēngzhào 000gb

Dōgen 111a Longchenpa 000g

We can illustrate the views and their attributes also in a table:

The existence of the B-series indicates the recognition of anisotropy and causality as ultimately existent, but the situation is different with the A-series, whose existence in a view is not necessarily indispensable for the conception of time as dynamic. This may seem contradictory, but in Longchenpa's case it can be seen that he affirms the dynamism of (timeless) time despite the absence of the A-series. We can also group the views according to the classification of analytic philosophy:

Time-denial – Nāgārjuna, Sēngzhào, Longchenpa

Presentism – Theravāda

Moving Spotlight – Sarvāstivāda, Dōgen

Looking at this summary, we have to say that Buddhist philosophy of time presents a relatively diffuse picture, with apparently no complete agreement on any aspect of time. What we do know is that Buddhism is a very diverse world religion, with many variations that have developed over the centuries. Yet, one might think that we might expect some kind of uniform answer to an important question like the nature of time, but apparently this is not the case. Why is there no unified Buddhist philosophy of time? One possible reason for this is that metaphysics is not an essential element in Buddhist philosophy but a kind of stowaway in the history of ideas, that emerges from time to time, and since it is not constrained by doctrines, it can be of many kinds, depending on the school of thought, the era, and the philosopher.

Or we can take a different approach, and we try to see the similarities between Buddhist philosophies of time, focusing on that and not on the differences. And perhaps we can sketch out a view of the nature of time that is common to the different schools. In looking for this greatest common divisor (or least common multiple) we see that from the six factors listed in the chart there isn't any in which all the six views agree. However, we can make a summary, according to which, the "average buddhist philosopher"...

- rather claims that past and future are non-existent, alongside with the B-series (66%),

- is uncertain about the real existence of the present and the A-series (50%),

- and rather thinks that time is dynamic than static (66%).

If we calculate which of the views in the table is the most typical, meaning which one differs the least from the other five views, then the result is that there are two views that differ from the others by an average of only 2.8 points, namely the Theravāda school and Longchenpa's Dzogchen-view. And the most extravagant, the one that differs in most respects from all the others, is the Sarvāstivāda school. Does this mean that Theravāda and Dzogchen think about time in "the most Buddhist" way? Certainly not. Every Buddhist philosophy is completely Buddhist. Secondly, this is just one view of the philosophy of time from a certain Western philosophical perspective, from the analytic philosophy, one could also look at the question from a different point of view (e.g. phenomenological or some other), obviously with different results. In any case, if we look at Buddhist views on time from this point of view, it is probably safe to say that Therāvada and Longchenpa would have the least disagreement with the other five philosophies. In addition, Longchenpa belongs to the group of time-deniers, which represents half of the opinions examined, and this is quite a high proportion. Nāgārjuna, Sēngzhào and Longchenpa described the traditional understanding of time as illusory, not part of ultimate reality. The reason is that for these authors, time, being not a separate entity but a relation, does not have an independent existence, but even as a separate entity, it would be devoid of inherent nature like all other entities in the perceived world.

But what is their explanation for the fact that we do assume time, consider it to exist, and think in terms of our concepts of time? The Buddhist answer to this is the same as to all other errors and misperceptions, which is innate ignorance. This ignorance, in the classical Buddhist understanding, is not a total intellectual darkness, but the lack of insight concerning the facts that things are impermanent, insubstantial and suffering-ridden. The origin of this ignorance is not really explained in Buddhism, except that it has always been ignorance, and its origin cannot be discovered, and the efforts to discover its origin are completely futile, see the analogy of the poisoned arrow.[149] Since this doctrine was expounded in the early phase of Buddhism, no philosophical works have been written about the origins of ignorance, so we don't know or are not interested in why we perceive time instead of timelessness – but we have the potential to change that.

In opposition to the time-deniers, the other three views are opinions in which the present has a privileged ontological position. Obviously, it is no coincidence that neither the past nor the future has this central role in any of them. The present moment has traditionally been given great importance in Buddhist non-philosophical texts, and it is a frequent subject of general Buddhist discourse, appearing often in dharma-talks and Buddhist teachings. The present moment is indeed of utmost importance, not only ontologically, but also soteriologically. For Longchenpa, the present moment is "from which" the timeless ground, the ultimate reality can be experienced. And even apart from him, all Buddhist authors, regardless of their school of thought, encourage concentration and meditation, in which we should focus on the present moment, so the unspoken primacy of the present seems clear. This is the point where philosophy and practice converge. It is perhaps not mere speculation to suggest that one reason for the distinctive ontological status of the present in Buddhist philosophy is the distinctive practical significance of the present in Buddhist meditation.

References

Abe, Masao 1992. A Study of Dōgen. His Philosophy and Religion. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Arntzenius, Frank 2012: Space, Time and Stuff. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bastow, David 1994. The Mahā-Vibhāsa Arguments for Sarvāstivāda. Philosophy East and West, 40(3): 489-499.

Bhikkhu Bodhi (tr.) 2007. The Discourse on The All-Embracing Net of Views: The Brahmajāla sutta and its commentaries. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society.

Bhikkhu Bodhi (ed.) 2010. A Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma. The Abhidhammattha Sangaha of Ācariya Anuruddha. Onalaska: BPS Pariyatti Editions.

Boucher, David – Vincent, Andrew 2012. British Idealism. A Guide for the Perplexed. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Bourne, Craig 2006. A Future for Presentism. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Casati, Filippo – Priest, Graham 2017. Inside Außersein. IFCoLog Journal of Logics and their Applications 4(11): 3583-3596.

Chan Wing-Tsit 1963. A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Chang Chung-Yuan 1974. Nirvana is Nameless. Journal of Chinese Philosophy, 1: 247-274.

Cox, Collett 1995. Disputed Dharmas. Early Buddhist Theories on Existence. An Annotated Translation of the Section on Factors Dissociated from Thought from Saṅghabhadra's Nyāyānusara. Tokyo: The International Institute for Buddhist Studies.

Dhammajoti, K.L. 2015. Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma. Hong Kong: The Buddha-Dharma Centre of Hong Kong.

Garfield, Jay L. 1995. The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way. Nāgārjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā. New York: Oxford University Press.

Garfield, Jay L. 2011. Taking Conventional Truth Seriously: Authority regarding Deceptive Reality. In: Cowherds, The (eds.) Moonshadows. Conventional Truth in Buddhist Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press, 23-38.

Guenther, Herbert V. (tr.) 1975. Kindly Bent to Ease Us: from The Trilogy of Finding Comfort and Ease. Ngal-gso skor-gsum. Emeryville: Dharma Publishing.

Heine, Steven 1983. Temporality of Hermeneutics in Dōgen's "Shōbōgenzō". Philosophy East and West 33(2): 139-147.

Ho Chien-hsing 2014. The Way of Nonacquisition: Jizang's Philosophy of Ontic Indeterminacy. In: Lin C. – Radich M. (eds.) A Distant Mirror. Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century Chinese Buddhism. Hamburg: Hamburg University Press, 397-418.

Ho Chien-hsing 2018. The Nonduality of Motion and Rest: Sengzhao on the Change of Things. In: Wang, Y.C. – Wawrytko, S.A. (eds.) Dao Companion to Chinese Buddhist Philosophy. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 175-188.

Ho Chien-hsing 2019. Ontic Indeterminacy: Chinese Madhyamaka in the Contemporary Context. Australasian Journal of Philosophy 98(3): 419-433.

Holder, John J. 2006. Early Buddhist Discourses. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

Jorgensen, John 2005. Inventing Hui-Neng, the Sixth Patriarch. Hagiography and Biography in Early Ch'an. Leiden: Brill.

Karmay, Samten Gyaltsen 2007. The Great Perfection (rDzogs chen). A Philosophical and Meditative Teaching of Tibetan Buddhism. Leiden: Brill.

Karunadasa, Y. 2010. The Theravāda Abhidhamma. Its Inquiry into the Nature of Conditioned Reality. Hong Kong: Centre of Buddhist Studies, The University of Hong Kong.

Kim, Wan Doo 1999. The Theravādin Doctrine of Momentariness. A Survey of its Origins and Development. PhD thesis. Balliol College, Oxford.

Le Poidevin, Robin 1991. Change, Cause and Contradiction. A Defence of the Tenseless Theory of Time. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Liu Ming-Wood 1994. Madhyamaka Thought in China. Leiden: Brill.

Lobel, Adam S. 2018. Allowing Spontaneity: Practice, Theory, and Ethical Cultivation in Longchenpa's Great Perfection Philosophy of Action. Doctoral dissertation. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Loux, Michael J. 2006. Metaphysics. A contemporary intoduction. New York: Routledge.

Mander, W.J. 2011. British Idealism. A History. New York: Oxford University Press.

McCall, Storrs 2001. Tooley on Time. In: Oaklander, Nathan L. (ed.) The Importance of Time. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, 13-19.

McLure, Roger 2005. The Philosophy of Time. Time before times. New York: Routledge.

McRae, John R. (tr.) 2000. The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch. Berkeley: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research.

McTaggart, J. Ellis 1908. The Unreality of Time. Mind, New Series 17(68): 457-474.

McTaggart, J.M. Ellis 1921. The Nature of Existence. Vol. I. London: Cambridge University Press.

McTaggart, J.M. Ellis 1927. The Nature of Existence. Vol. II. London: Cambridge University Press.

Miller, Kristie 2017. A Taxonomy of Views about Time in Buddhist and Western Philosophy. Philosophy East and West, 67: 763-782.

Nakamura, Hajime 1983. A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Newland, Guy Martin 2011. Weighing the Butter, Levels of Explanation, and Falsification: Models of the Conventional in Tsongkhapa's Account of Madhyamaka. In: Cowherds, The (eds.) Moonshadows. Conventional Truth in Buddhist Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press, 57-74.

Newland, Guy – Tillemans, Tom J.F. 2011. An Introduction to Conventional Truth. In: Cowherds, The (eds.) Moonshadows. Conventional Truth in Buddhist Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press, 3-22.

Oaklander, L. Nathan 2020. C.D. Broad’s Philosophy of Time. New York: Routledge.

Prasad, Hari Shankar 1982. The Concept of Time in Buddhism. Ph.D. thesis. Australian National University.

Raud, Rein 2012. The Existential Moment: Rereading Dōgen's Theory of Time. Philosophy East & West 62(2): 153-173.

Ronkin, Noa 2005. Early Buddhist Metaphysics. The making of a philosophical tradition. New York: RoutledgeCurzon.

Rundle, Bede 2009. Time, Space, and Metaphysics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schilbrack, Kevin 2000. Metaphysics in Dōgen. Philosophy East and West 50(1): 34-55.

Sharma, Ramesh Kumar 2015: J.M.E. McTaggart. Substance, Self, and Immortality. London: Lexington Books.

Sider, Theodore 2001. Four-Dimensionalism. An Ontology of Persistence and Time. New York: Oxford University Press.

Siderits, Mark 2022. How Things Are. An Introduction to Buddhist Metaphysics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Siderits, Mark – Katsura, Shōryū 2013. Nāgārjuna's Middle Way. Mūlamadhyamakakārikā. Boston: Wisdom Puplications.

Skow, Bradford 2015. Objective Becoming. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stambaugh, Joan 1990. Impermanence Is Buddha-nature. Dōgen's Understanding of Temporality. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Steineck, Christian 2007. Time is not fleeting: Thoughts of a Medieval Zen Buddhist. KronoScope 7: 33-47.

Szegedi Mónika 2018. Vaszubandhu Abhidharma-kósája: ontológia és kozmológia. A buddhista atomizmus. Doctoral dissertation. Budapest: Eötvös Loránd University.